Paintings & Works on paper

About

Sébastien Bertrand is pleased to present an exhibition of paintings by Walter Robinson and drawings by Francis Picabia, exploring how both artists probed themes of romance, desire, and mass culture through their appropriation and recontextualization of commercial imagery.

In the 1980s, the resurgence of representational art, along with debates over authenticity pursued by Pictures Generation artists, rekindled interest in Picabia’s work, particularly his “Transparencies” and notorious 1940s “kitsch” paintings. While he has since been paired with artists such as David Salle, Julian Schnabel, and Sigmar Polke, this exhibition is the first to foreground the formal and conceptual parallels between Picabia’s drawings of women and Robinson’s “romance” paintings.

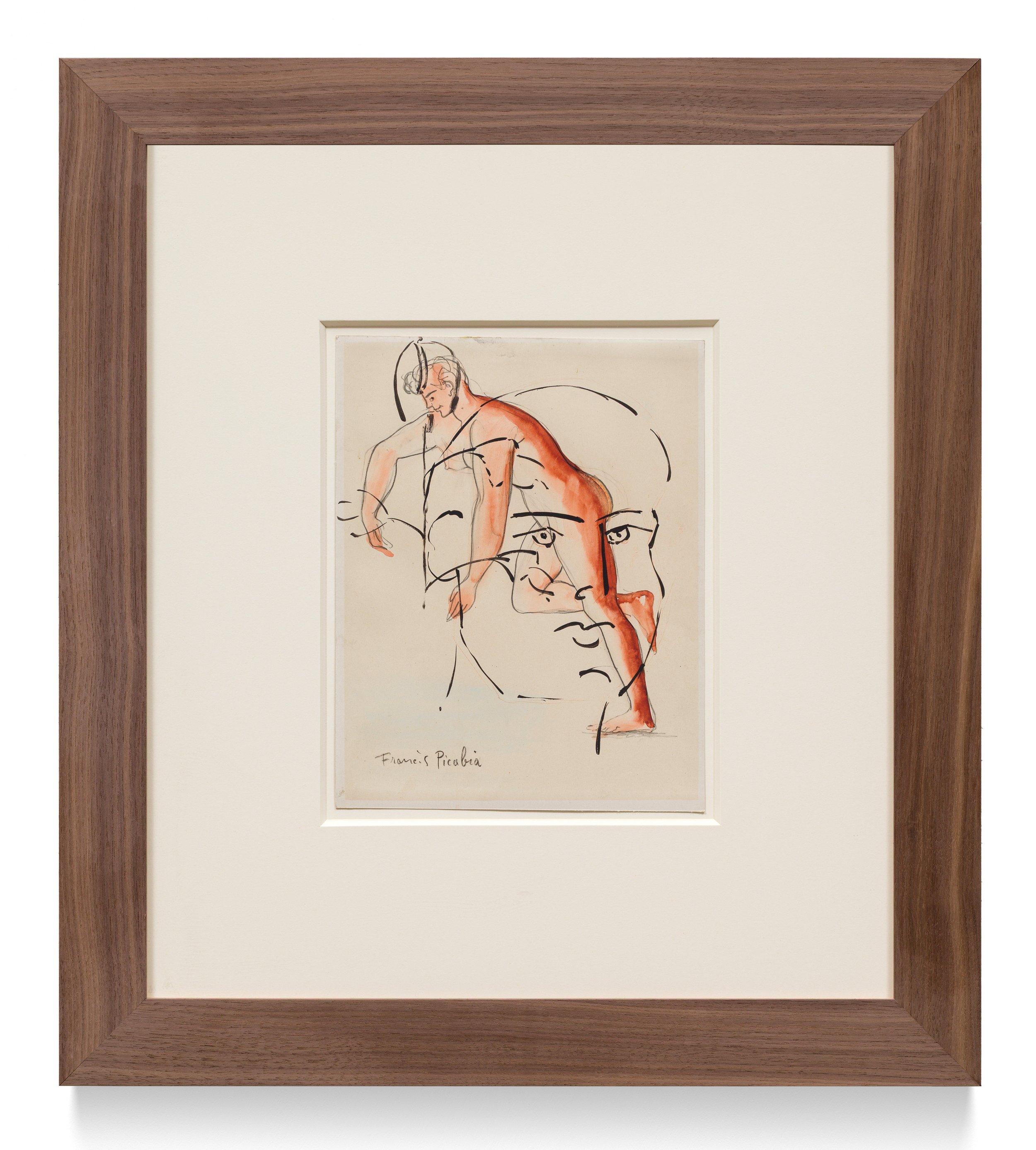

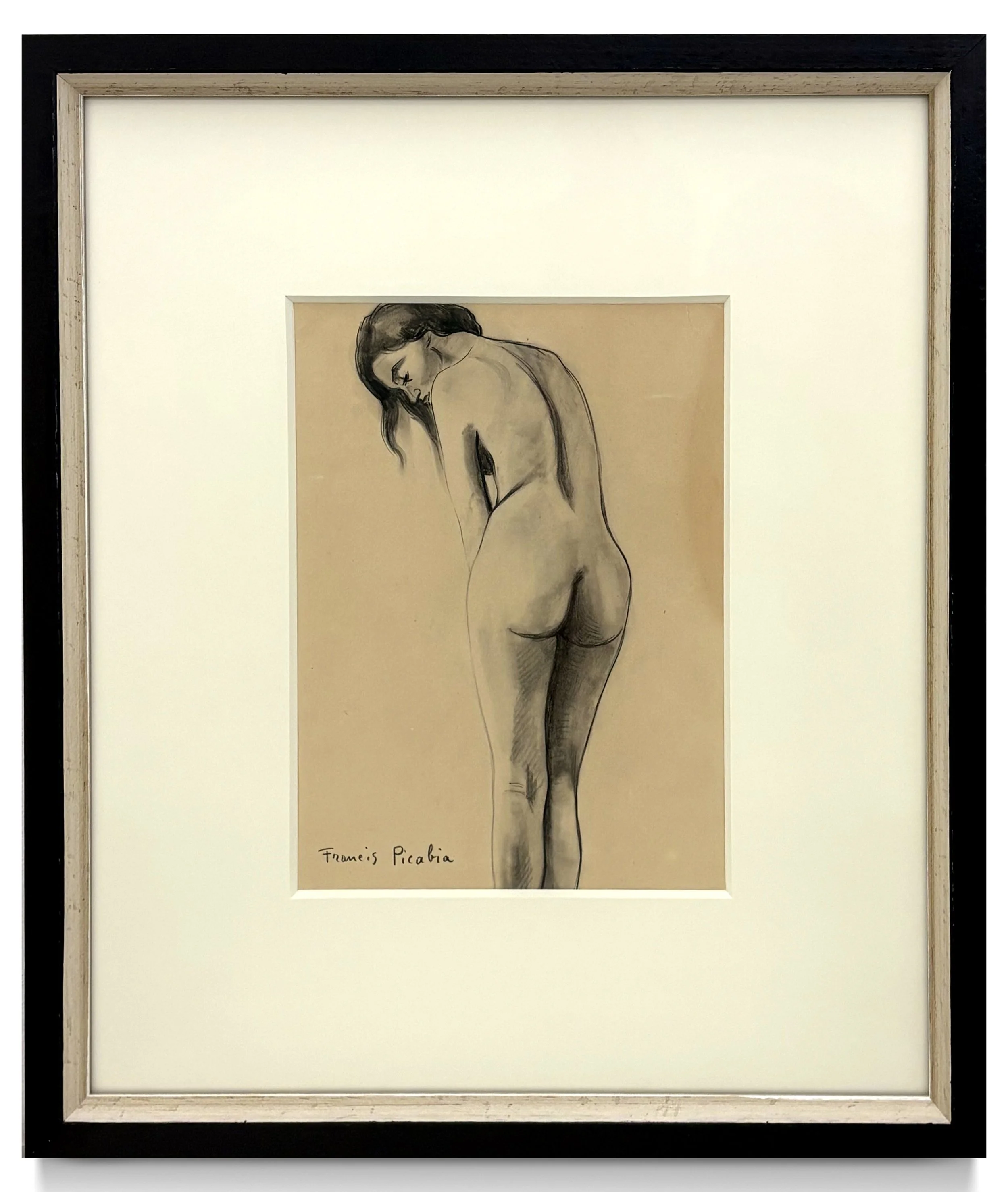

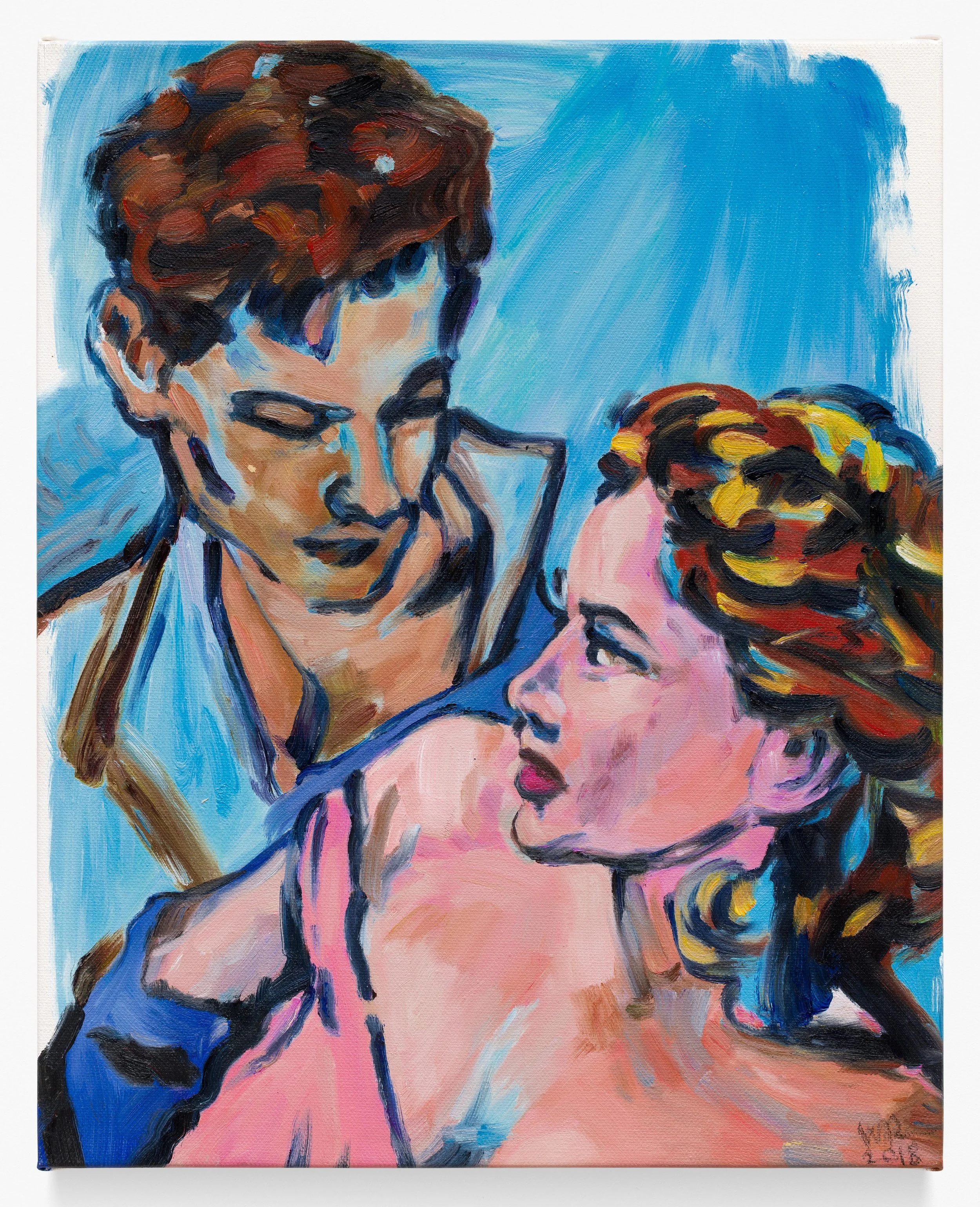

Both artists mined commercially reproduced images with deliberate indifference to hierarchies of taste. Classically trained yet radically unorthodox, Picabia was among the first artists to work almost exclusively from photographic sources: postcards, engineering illustrations, movie-magazine photographs, and softcore pornography. Decades later, Robinson treated pulp paperback covers, film posters, advertisements, and product packaging as a collective archive of fantasy and desire. By “side-stepping the need for a personal, original style,” he sought to “focus attention away from formalist issues and onto questions of content.”

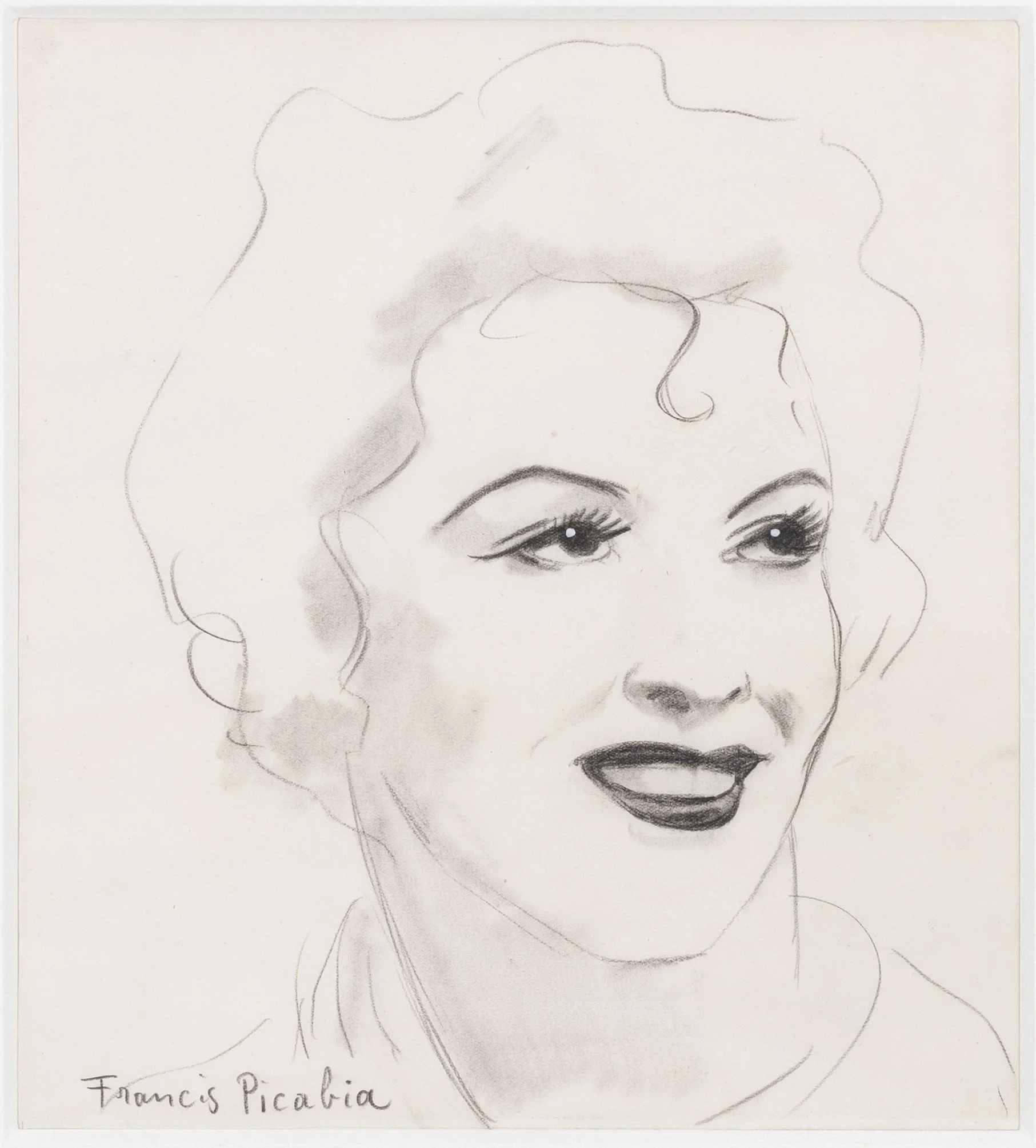

Romance in Robinson’s paintings is never benign. His couples hover on the brink of betrayal, danger, or violence, echoing the lurid narratives of his pulp fiction sources and the aesthetics of film noir. In The Eager Ones (2025), a reprise of one of his earliest paintings, entwined lovers rendered in quick, economical brushwork nearly burst beyond the edges of the canvas, their desire inseparable from menace. Picabia’s figures, by contrast—as in J'interroge le sphynx…, 1927—appear emotionally detached even when physically conjoined, effecting an eroticism that is cool, uncanny, and strangely impersonal. A similar aloofness characterizes his “head shot” drawings of movie stars and dreamy-eyed models copied from popular Parisian magazines.

The two artists readily embraced change throughout their careers. Picabia, the consummate shapeshifter who proclaimed, “If you want to have clean ideas, change them as often as your shirts,” produced what Marcel Duchamp called a “kaleidoscopic series of art experiences.” Robinson likewise moved restlessly across genres—from pulp romance to pharmaceuticals, spin art, pornography, TV dinners, fashion, and burgers—often revisiting earlier motifs as if to test their durability across time.

Language also played a crucial role for Picabia and Robinson, both as imagemakers and as writers, editors, and publishers. Picabia included typeset titles in his Dadaist “mechanomorphs” and integrated handwritten, absurdist phrases into many of his drawings. Robinson’s approach was sly and conceptual: he borrowed his paintings’ titles directly from the paperback covers and advertising captions he appropriated. Picabia, a prolific poet, published 391, a Dadaist journal featuring his and his peers’ artwork and poetry. Robinson, a celebrated writer, co-founded Art-Rite, an influential magazine comprising critical texts and artist-designed pages. He was also the founding editor of artnet, the first online art magazine.

Exhibited side by side, works by Walter Robinson and Francis Picabia reveal that recycled images of romance and eroticism are persistently compelling, that the act of painting and drawing remains a potent site for questioning how mass culture shapes, distorts, and sustains our most intimate longings.

— Barry Blinderman

Francis Picabia, Portrait de femme de trois quart, c. 1940-42

Pencil and gouache on paper, signed lower left., 26 x 23.5 cm., 10 1/4 x 9 1/4 in. (FP-4042)

Walter Robinson, Untitled, 2025

Acrylic on canvas, 40.6 x 40.6 cm., 16 x 16 in. (WR-2512)

c. 1940-42

Pencil and gouache on paper

26 x 23.5 cm. / 10 ¼ x 9 ¼ in.

FP-4042