Ode to Sad Disco

Sébastien Bertrand is pleased to present “Ode to Sad Disco” a group show bringing together works by Joe Andoe, Pierrette Bloch, Sylvie Fleury, Lucio Fontana, Thomas Fougeirol, Vera Molnar, Loïc Raguénès, Robert Ryman, Sean Scully, Thomas Schütte, Niele Toroni, which invite the viewer on a journey through abstraction, repetition and imprints.

Like the famous ‘Pêche miraculeuse’, the first painting to combine a realistic landscape with a religious scene, the history of painting in Geneva betrays an unorthodox taste. The same is true of the major exhibitions that have marked the city of Calvin, such as ‘Abstract Painting’, for which John Armleder (*1948) in 1984 brought together painters as different as the concrete Loewensberg (1912‑1986) and the surrealist Schnyder, or the spatial depth and non‑illusionist surface with Fontana (1899‑1968) and Ryman (1930‑2019).

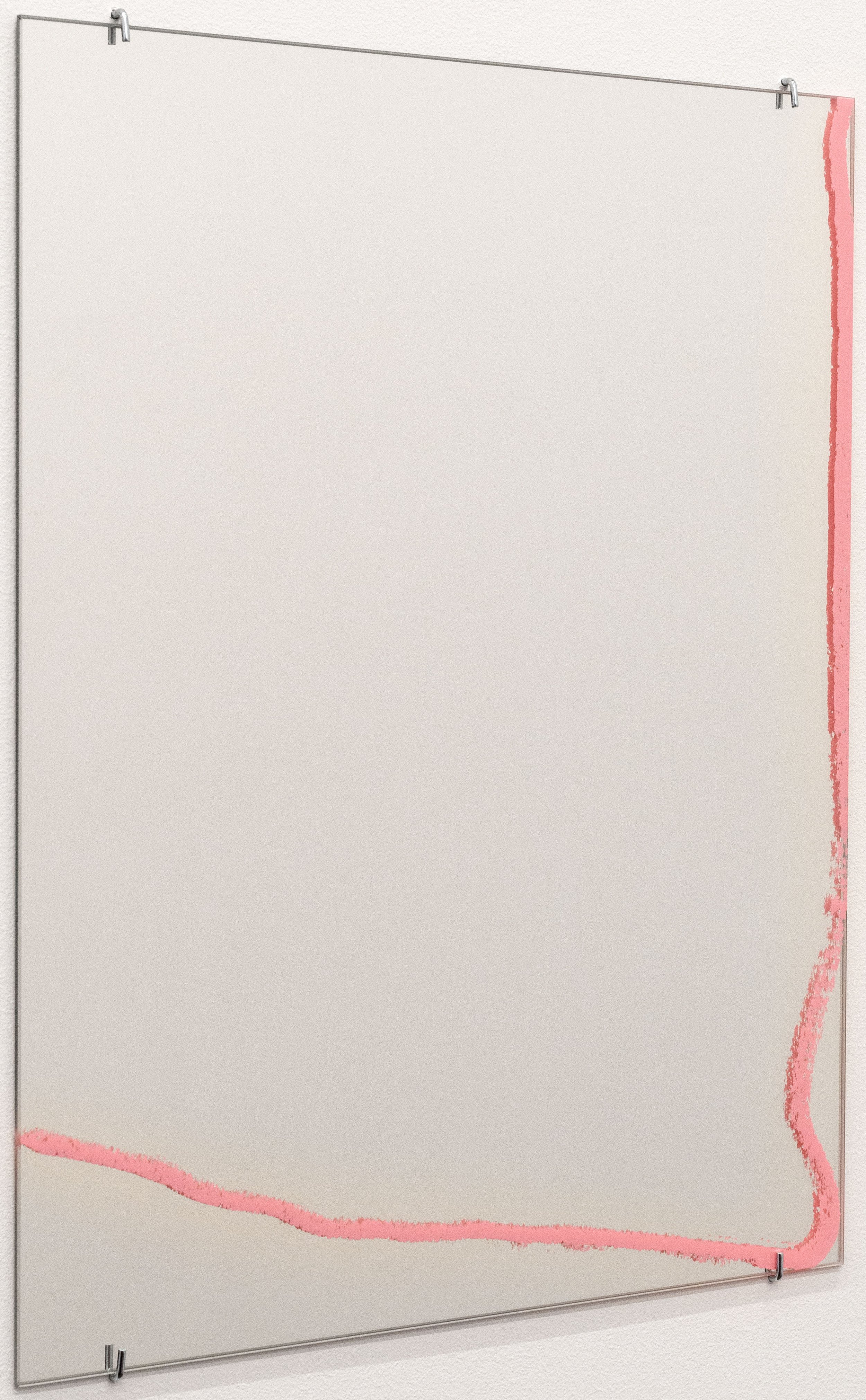

It is precisely with these two artists that Sébastien Bertrand designed an exhibition in the form of an ellipse, a dizzying classification of painting, and an extended typology ranging from text to abstraction. In this arc, ‘matiérisme’ is by turns regressive or modernist, with the promise of a sign and the threat of a hole.

Although Robert Ryman began painting in the mid‑1950s, his exhibition at the Guggenheim established his reputation in 1971. To better understand his dynamic conception of monochrome, let us quote the painter on his first recorded painting, dating from 1959: “I’ve always thought that if I ever wanted to paint a white painting it would be in the order of the way this painting was done, because this is definitely an orange painting but there are many nuances and many oranges (and black and green) . And if I were doing a white painting, I would approach it the same way, and there would be whites and warm‑whites and cold areas and then you would have a white painting.” [ 1 ]

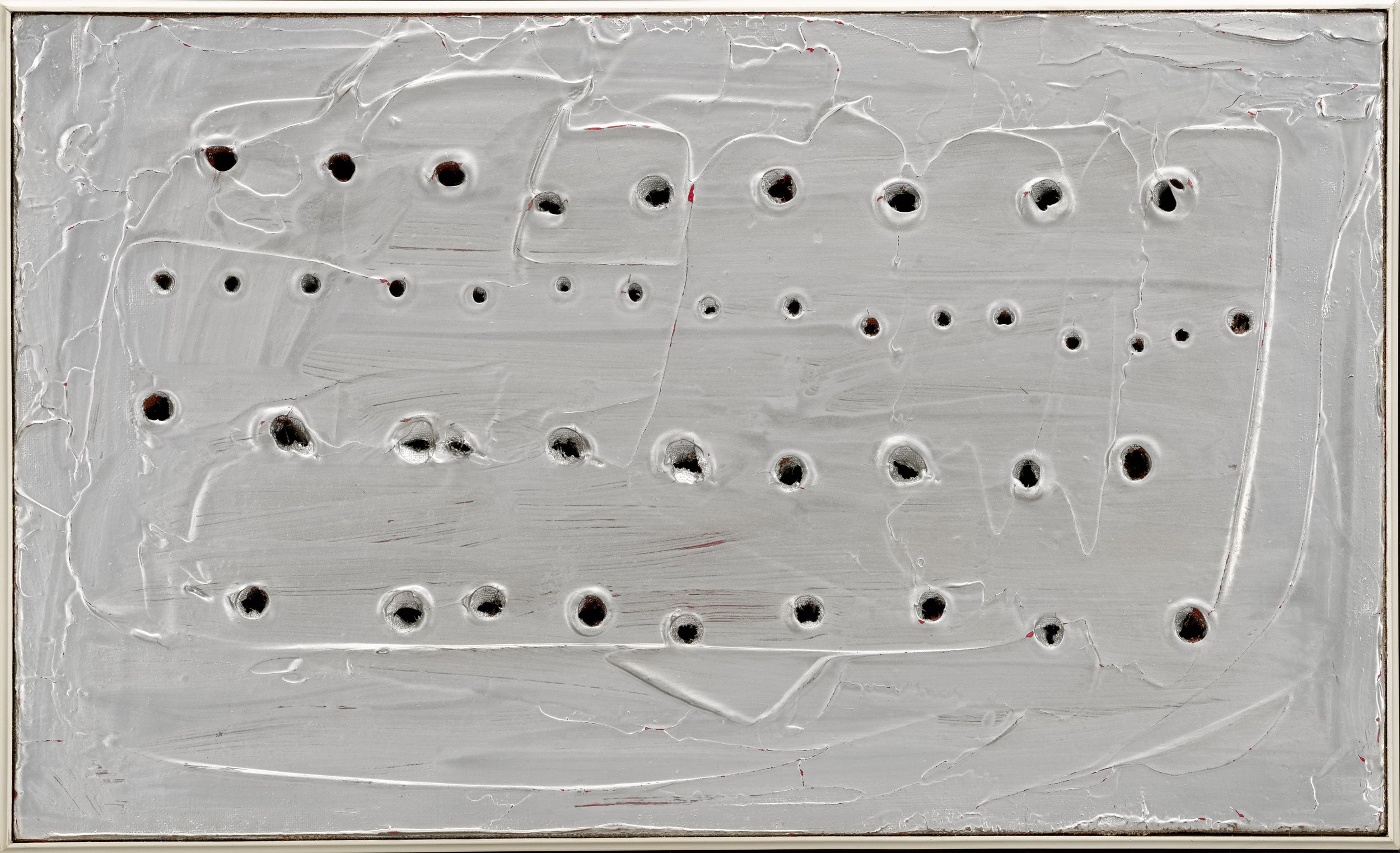

With Lucio Fontana, “it’s hard to see the work as part of a projection based on the modernist model of figuration and abstraction”. For Fontana, “the canvas is there first and foremost, not for what it represents, but to designate that through which we can see. He wants to be the seer. The torn canvas designates the infinite.” [ 2 ]

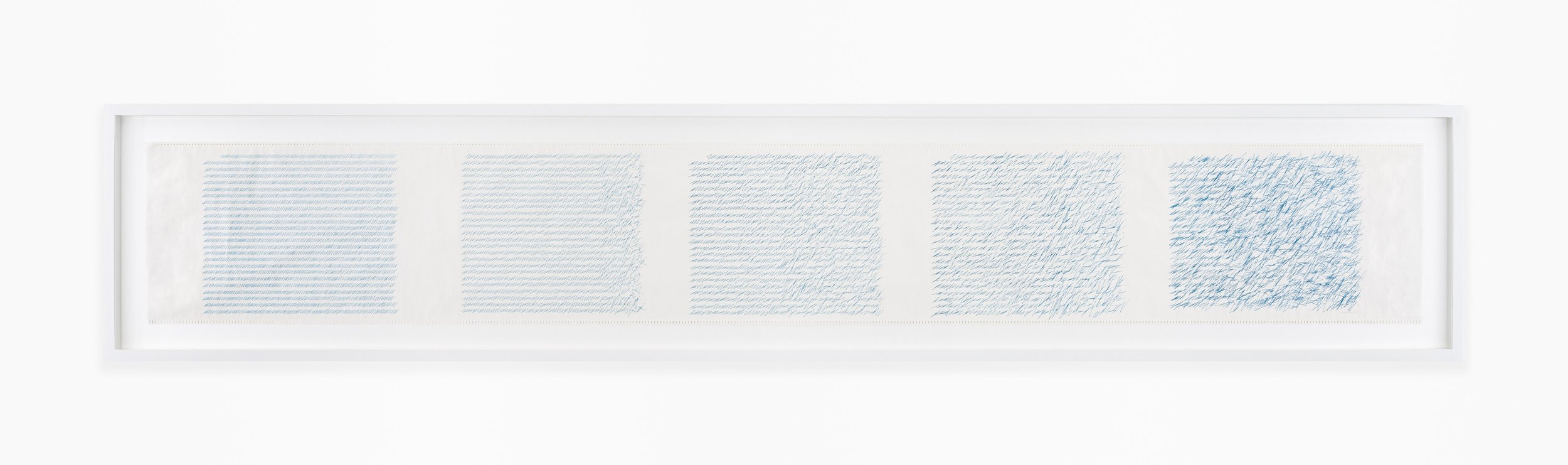

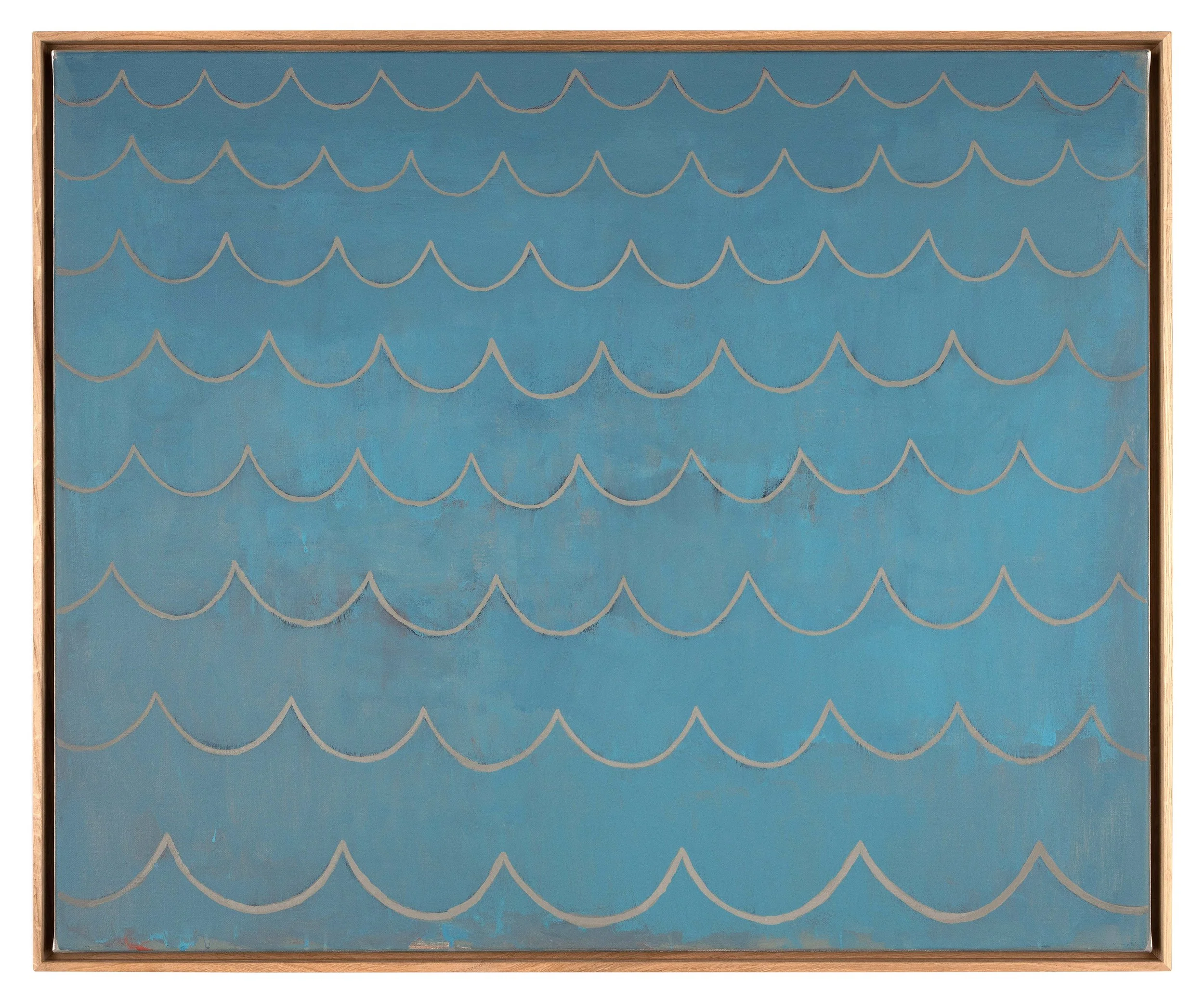

What direction are the artists brought together by Sébastien Bertrand looking in? There is indeed deep space in the grained surface of Thomas Fougeirol (*1965), just as Joe Andoe (*1955) evokes a Ruysdael (1628‑1682) whose climatic charge is so heavy that the horizon seems to be pushed out of the painting. There is something sublime in the marine by Loïc Raguenes (1968‑2022), so much so that we want to believe in even the stereotyped lines of the waves, while in Pierrette Bloch (1928‑2017) (the only Swiss artist in the exhibition) we want to see a language that is irreducible to the verb. Treating all the artists in the exhibition too quickly would be unfair.

In this journey from the scriptural to the iconoclastic, it would be unfortunate to fall into the modernist trap of polarizing sacred and profane, figuration and abstraction, and let us prefer a form of painting that Beckett described as ‘of impediment’, freed from formal perfection to aim – in an absurd world – for emancipation: “The client: God made the world in six days, and you can’t make me a pair of trousers in six months”. The tailor: “But, Sir, look at the world, and look at your trousers!”. [ 3 ]

[ 1 ] Tate, MoMA, 1993.

[ 2 ] Mnam, CGP, 1988.

[ 3 ] Samuel Beckett, Le monde et le pantalon: suivi de Peintres de l’empêchement, Éditions de Minuit, 1989.

Loïc Raguénès, Baliste Cabri, 2020

Tempera on canvas / 66.7 x 81.2 cm. / 26 ¼ x 32 in. LR-2001

Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale, 1960

Oil, holes and silvery varnish on canvas / 27 x 44.7 cm. / 10 ¾ x 17 ½ in.

LF-6001

1965

Oil on linen

23.5 x 23.5 cm. / 9 ¼ x 9 ¼ in.

RR-6501