Still Life: An Ongoing Story

About

We are pleased to present this group exhibition which has been a priority project for the gallery for some time.

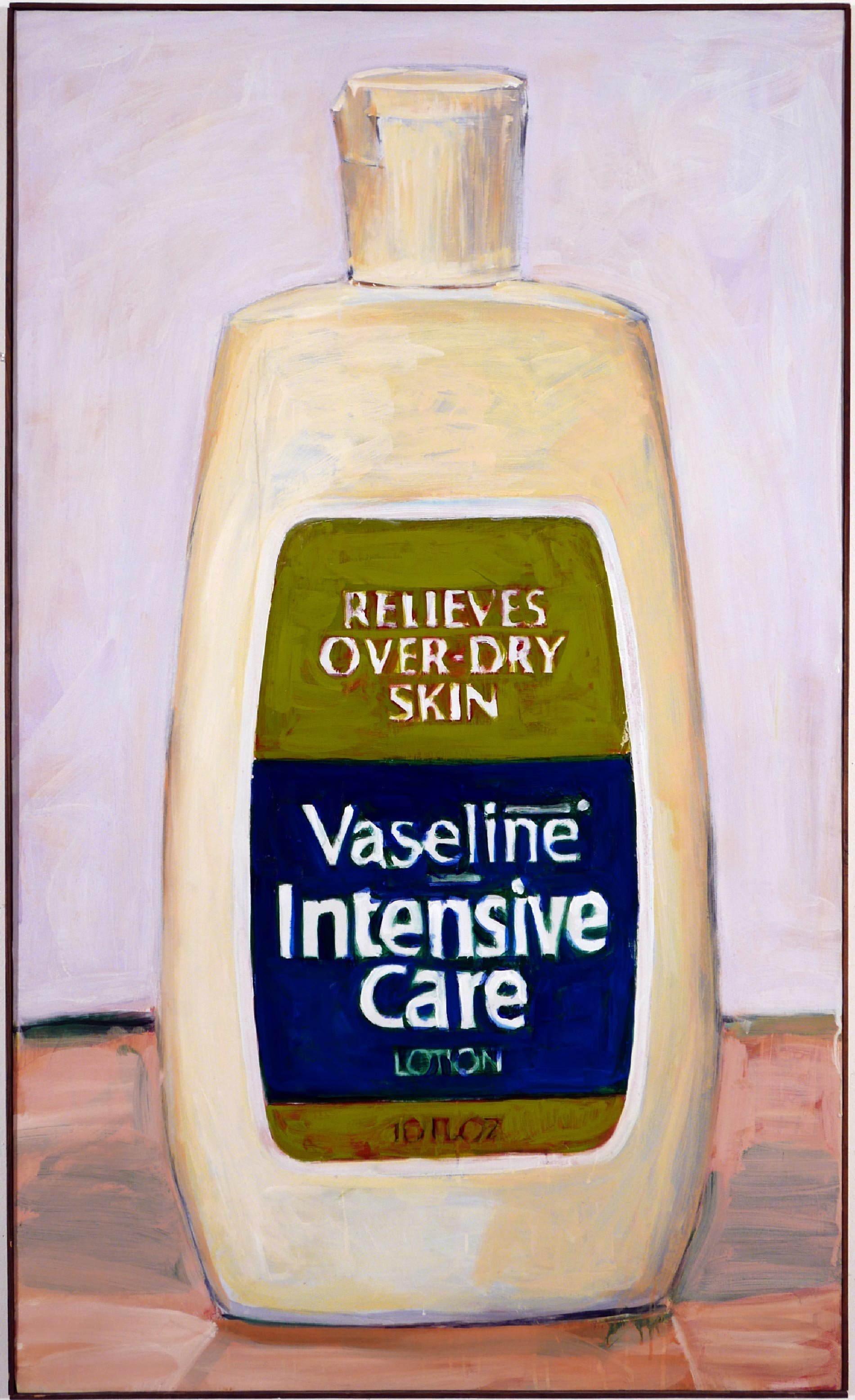

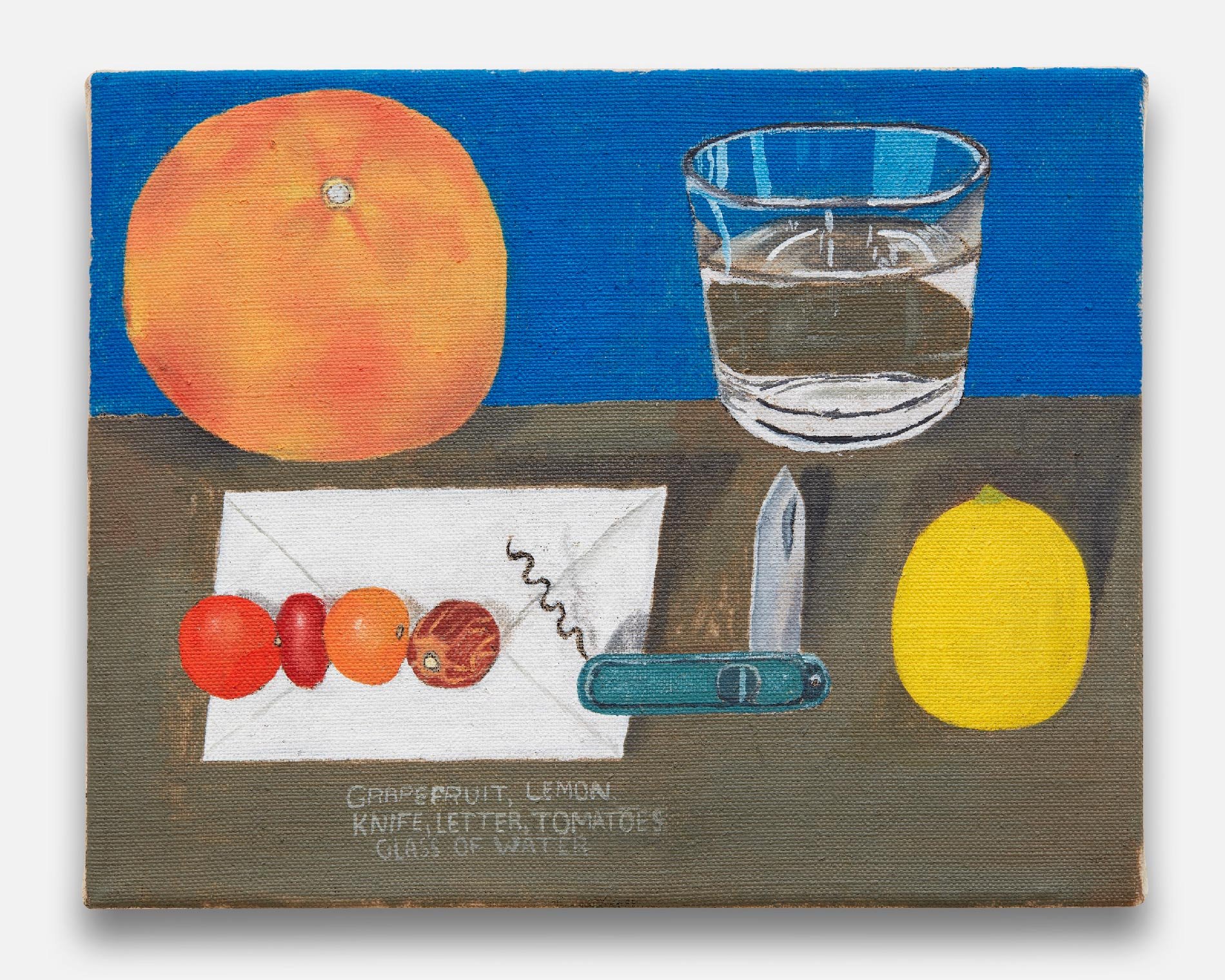

The theme of Still Life, from Antiquity to the present, primarily involves assembling or presenting objects in compositions that intensify their symbolic meanings. This symbolic dimension of objects was first religious in the Middle Ages (but this category is not recognized by some), then became philosophical, secular and cultural when the genre was developed in 17th century in the Netherlands, in the pomp of the time and the accumulation of decorative objects. At that time, it reflects the abundance and prosperity of this period.

Religious morality was gradually diluted in the evolution of morals, progress and enthusiasm for science, discoveries (especially botanical) from overseas exploration and their scientific illustrations. Artists became reconciled with Nature and objects in themselves, and then the aesthetic preoccupation gradually took over. Nevertheless, the genre has long been considered a minor one.

According to Margit Rowell, the domestic content of the still life caused the genre to be relegated to the bottom of the ladder, similar to “women’s work,” mainly because it portrays content and spaces considered to fall within feminine matters, this argument being sufficient for it to be judged unworthy of interest. This gives special meaning to how women artists revisited the genre in the course of history.Despite these reductive considerations, the still life has remained attractive to artists of all times and movements, probably because it contains specific qualities, such as the highly revealing scope of these objects of a specific time and society, and the relationship that society has with these objects.

“The process of selection is traditionally influenced by the role certain objects play in the context of a given society. Although the objects are relatively generic, as subjects they are not timeless; their choice is dictated by their place, be it passive or aggressive, in a historical and cultural fabric. (…)These works (like all artworks) do not depict the real or the natural but are cultural signifiers, and the codes by which they operate are not spontaneously invented and reinvented but ideologically determined, not personal to the artist but strategically symbolic of the priorities and desires of a given society at a given time.” — Margit Rowell, Objects of Desire: The Modern Still Life, The Museum of Modern Art, 1997

This can be seen quite clearly from the genre’s beginnings, when artists worked mainly on orders placed by the bourgeoisie. From the 20th century, the avant‑gardes complicated this relationship to the object by distancing themselves from bourgeois values and sponsors, by introducing their own narrative and their personal relationship to objects. It was still a reflection of a social structure, but the place of artists in this structure and thus their viewpoint had changed. Since the still life was not subject to as many aspirations as other more highly valued genres (portraiture, landscape or history painting), it became the perfect tool for contemporary expression of these avant‑gardes in search of freedom.

“This narrowly circumscribed genre has to this day been locked into a definition (or rather a perception) based on its lowest common denominator, the inanimate commonplace object, and yet, precisely because of this consistent and presumably unadventurous subject matter, the still life has lent itself to all manner of adventurous visual interpretation.” — Margit Rowell, Objects of Desire: The Modern Still Life, The Museum of Modern Art, 1997

Since the still life achieved its recognition over the course of history, it seems that precisely its classical and respectable aspect, a reflection of a past time, arouses the interest of artists who can revisit it today carrying the baggage of the 20th century’s formal deconstruction.

While integrating the works of these different periods, however, we never have a feeling that time jumps back and forth. Rather, we feel able to visualize this secular genre and retrace it as a path without discontinuities, as an ideal and natural way of reading the history inside History. A history of objects, but more than anything a history of our relationships with objects and thus the economic, political and aesthetic issues that underpin them.

Featuring works by: Alfredo Aceto, Andries Daniels, Che Lovelace, Cornelis Mahu, Elad Lassry, Georg Dionysius Ehret, Hannah Rowan, Jan Van Kessel, Jesse Wine, Joe Andoe, John Armleder, Lynnea Holland‑Weiss, Michael Hilsman, Paulo Wirz, Richard Kern, Roman Signer, Storm Tharp, Sylvie Fleury, Todd Bienvenu, Walter Robinson, Yarisal & Kublitz

Walter Robinson, Anonymous Cheeseburger, 2018

Yarisal & Kublitz, Another Peel, Another Deal, 2014

2019

Ink, gouache and fabric dye on Gampi

118 x 89,5 cm / 46,5 x 35,2 in.